In many of the information technology leadership searches Spencer Stuart conducts, clients express interest in placing more women in senior roles, often citing the benefits of having a diverse organization. Yet, the function traditionally has attracted fewer women and been less successful in advancing women to leadership positions than other functions.

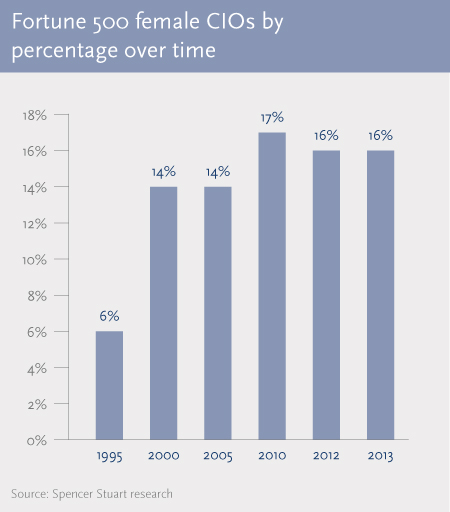

By one measure, women have made progress: The number of female chief information officers in the Fortune 500 has more than doubled since 1995 — from 28 female CIOs in 1995 to 76 in 2013. Nevertheless, only 16 percent of Fortune 500 CIO positions are held by women, a decline from 17 percent in 2010. After significantly increasing in the late 1990s, the representation of women in the top IT role seems to have plateaued in the past decade.

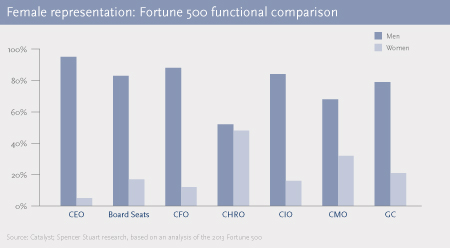

IT, of course, is not the only functional area where women are underrepresented in leadership roles. Just 5 percent of Fortune 500 CEOs and 12 percent of CFOs are women. However, women represent 17 percent of board directors, 21 percent of general counsels, 32 percent of chief marketing officers and almost half — 48 percent — of chief human resources officers.

And it isn’t just the top IT role where the lack of female representation is notable. While women held 57 percent of professional jobs in the U.S. in 2012, only 26 percent of professional computing jobs were held by women, according to the National Center for Women & Information Technology.

Proponents of improving the representation of women in IT argue that the lack of diverse perspectives can inhibit innovation, productivity and competitiveness. Furthermore, the comparative lack of women in IT may deprive U.S. companies of a potentially important and much needed source of technology and computing talent in the coming years.

The gap between the sexes in IT begins at school; while 57 percent of undergraduate degree recipients in 2011 were female, only 18 percent of computer and information sciences undergraduate degree recipients at major research universities were women. The National Center for Women & Information Technology also notes a 64 percent decline between 2000 and 2011 in the number of first-year undergraduate women interested in majoring in computer science.

The gap becomes more pronounced over time. Dr. Jane LeClair, dean of the School of Business and Technology at Excelsior College, has written that more than half of women working in technology (56 percent) leave the field in the middle of their careers, attributing the departures in part to a “glass maze” that can make it challenging for women to maneuver confusing practices in the male-dominated culture of some high tech environments. In addition, some women tire of being one of very few women in IT teams or leave because of work-life balance concerns.

Closing the gap

Efforts are being made to close the gap both in schools and the workforce. A number of programs have been created to teach computer science to high school and middle school girls and encourage them to pursue a degree in the field.

Meanwhile, companies of all sizes have noted the imbalance and established programs to recruit and keep more women in IT. The business press has noted some of these efforts:

- The e-commerce company Etsy invited a couple dozen women to a three-month intensive coding program dubbed Hacker Schools, many of whom were later recruited to work as engineers at the company.

- American Express hires college graduates for entry-level IT and project management roles for an 18-month program intended to help them build technical and leadership skills; women make up more than 30 percent of the company’s technical workforce.

- IBM encourages female employees in technical roles to use their networks to refer other women to the company; the connections account for as many as 30 percent of its professional female hires. The company also ties manager compensation and assessments to female recruitment targets.*

Beyond these more strategic initiatives, companies can make tactical moves aimed at increasing the participation of women, for example requiring at least one woman to be interviewed for every IT job opening, establishing a blind resume screening process to reduce the potential for unconscious bias, and measuring and evaluating female recruitment efforts.

Furthermore, several of the growth areas in technology — project managers, business analysts and web developers, for example — do not require computer science degrees and may attract strong female executives from other functions to these IT roles.

Like our clients, Spencer Stuart believes that diversity of perspectives contributes to a more complete understanding of issues and opportunities and fosters better decision-making. In the past three years, 33 percent of Spencer Stuart’s information officer placements were diverse candidates; 13 percent were women. It is an issue that we are passionate about and one in which we will continue to invest time, effort and energy. In particular, we consistently evaluate the tools, networks and conversations that are most meaningful in attracting diverse technology leaders. With this interest in mind, we would welcome any and all feedback on how your organization is responding to the need for female IT leaders. We plan to play an ongoing role in this endeavor and look forward to partnering with our clients and candidates to change the IT talent landscape.

* “Closing IT’s Gender Gap.” July 2012. PM Network.^