Family values

You must ensure that you are developing what the organization stands for and how the organization is going to live up to its vision and values.

Values are the glue that binds the family, the business and its employees. They usually reflect the founder’s philosophy and act as a guide to “the way we do business”. Sometimes they are enshrined in statements of ‘core values’ that are frequently referred to in company communications and that underpin day-to-day decision-making. “Our values go back almost 20 years and still define our business,” says Torben Østergaard-Nielsen, CEO of United Shipping and Trading Company (USTC). “We don’t employ people who cannot identify with our values.”

Mohammed K.A. Al-Faisal, president of Al Faisaliah Group Holding, is also clear that creating an effective culture involves translating values into action. “I am not happy with our values until we actually put the application of those values into the annual remuneration calculation of senior management, myself included.” A few years ago, while addressing problems inside one of the Group entities, Mohammed K.A. Al-Faisal discovered that the company’s values meant different things to different members of the management team. So, it became necessary to articulate three to five actionable items under each one of these values. “One of our values is ‘ethics and integrity’; it is not open to interpretation,” he says. “We told people that we only need five things from you. First, we don’t lie, cheat or steal; second, we respect ourselves and respect others; third, we treat others how we want to be treated; fourth, we never talk badly behind another’s back; and fifth, we admit mistakes and correct them. If you have done these five things, in our eyes, you have lived up to the ethics and integrity value.” As Korsager Winther says, “Values are fine, but it’s the way you live them and the stories you tell to illustrate them that really matters.”

Values are closely linked to culture, but they are not the same thing. Understanding the distinction can make it easier to uncouple them when the business context changes.

The role of the board in

overseeing culture

It is important for the board of a family business to understand the role

organizational culture plays in business performance. Because culture

is a key driver of business results, the boards should ensure that it has

an adequate line of sight on the culture, including any potential risks the

culture could pose. Here are some questions they can ask to assess the

impact of culture:

-

What is the current culture of the organization?

-

How well aligned is our company’s culture with our strategy?

-

What is the difference between our current and ideal company culture?

-

How do we consider culture in our leadership succession planning?

-

How can the board contribute to the right tone at the top?

Distinguishing culture and values

There is a saying that “families have values and companies have cultures”. Values are highly personal and, in a family context, result in shared beliefs, attitudes and ideals that can permeate a business.

There is a fine line between someone who is resistant to change or someone that has an opinion that you are not willing to accept. You need to have someone that will give you a certain level of discomfort.

The values of a family business are invariably built off the core values of the founder. Over time they are amplified by family members, whether they sit on the family council, the board or the management team. Companies may need to dust their values off and reinvigorate them from time to time, but our experience is that most successful multi-generational family businesses are effective at preserving their foundational values and championing them across the enterprise. “Values have to be both credible and consistent,” writes Colin Meyer, Peter Moores Professor of Management Studies at the Saïd Business School in Oxford. “They have to be believed and enduring. They have to stand the test of time — for better for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health.”

A company’s culture, at its best, is an outward manifestation of its values. At Spencer Stuart, we define culture as:

The tacit social order of an organization: It shapes attitude and behaviours in wide-ranging and durable ways. Cultural norms define what is encouraged, discouraged, accepted, or rejected within a group. When properly aligned with personal values, drives, and needs, culture can unleash tremendous amounts of energy towards a shared purpose and foster an organization’s capacity to thrive.”*

Culture has a powerful effect on business results, helping to make or break even the most insightful strategy or the most experienced executives. It can encourage innovation, growth, market leadership, ethical behaviour and customer satisfaction. On the other hand, a misaligned or toxic culture can erode business performance, diminish customer satisfaction and loyalty, and deflate employee engagement.

*‘The Leader’s Guide to Corporate Culture’, Boris Groysberg, Jeremiah Lee, Jessa Price, and

J. Yo-Jud Cheng, Harvard Business Review, Jan-Feb 2018.

Changing the culture

Whereas values are constant and provide the underpinnings of a family business, culture is necessarily more pliant; it is a catalyst for performance and yet it must evolve over time. The company culture needs to be able to adapt in line with a changing strategy. Since every company has to revisit and upgrade its strategy (with increasing frequency and urgency in the current climate), it must also devote time and energy to examining whether its culture is up to the task of delivering on the strategy.

Even the best laid strategic plans will go to waste if the organizational culture is not aligned to the changing context, realities and goals of the business. When alignment is missing, culture eats strategy for breakfast, as the saying goes.

Even before the coronavirus pandemic, the world was in a constant state of flux as new technologies appeared, consumer behaviours changed and business models were upended. When leaders take their companies in a new strategic direction they need their organizations to respond. When transformation is required, the biggest barrier companies face is often their culture.

Cultural change is daunting, especially when the current culture has served an organization well for many years. Grundfos has a strongly rooted culture of social responsibility; for example, three to five per cent of its workforce has ‘reduced work ability’. According to CEO Mads Nipper, experience is highly valued and the company invests heavily in training. Like many family businesses it has always taken a long-term view. But whereas it might once have been able to invent a new hydraulics technology and have the market to itself for many years, competitors today are far quicker to respond, especially those in China. “Today, everything is about speed, about being fast to develop and deploy new initiatives. That’s where our culture works against us,” he says. “The world, thankfully, is moving in the direction of taking more long-term decisions, and so should we. But the execution of those things needs to be faster — not five or ten per cent faster, but twice as fast.” For Grundfos, this has meant adopting completely new ways of working that were foreign to the culture — overlapping processes, more self-guiding teams and a high degree of empowerment for ‘on-the-fly’ decision making.

Nipper created a digital transformation office, a semi-independent unit at HQ which gathered people from across the company to work on digitally enabled projects. He invited an entrepreneur with digital transformation experience to come in and lead the unit, but he wanted to avoid sending out a signal that cultural change could only come by importing talent. “Digitalization is for everybody. In my opinion, it’s wrong to assume that somebody who has worked in a strong culture for 20 years is by definition unable to change. I find that our most tenured employees are among the most curious and willing to adapt. If you are a 60-year old hydraulics engineer and you want to get involved on a digital project, you have the opportunity to do so. And by bringing together younger and more experienced staff everyone can learn from each other.”

Different, more agile processes were essential for Grundfos to retain its competitive edge. They could not be embedded in the organization without cultural change. This change was made easier by values of inclusivity and fairness and by a shared belief in the mission and social purpose of the business.

Østergaard-Nielsen says that culture has been a frequent topic for discussion in meetings of the board and the family council, most recently as part of a major restructuring involving changes to the business model and supplier and customer relationships. “Having the right culture profile enables us to charge more for our services,” he says.

Towards a learning culture

Organizational transformation tends to accelerate during a crisis. Change programmes that might have taken years under normal circumstances are being implemented rapidly, an obvious example being the mass shift towards working from home caused by the coronavirus. One of the disadvantages of deeply embedded cultures with their long-established ways of working, habits and behaviours, is that they can be found wanting during a period of upheaval. Unless, that is, they also have a bias towards learning agility.

We see a number of cultural shifts taking place in family-owned businesses: for example, a move away from patriarchal, hierarchical and authority-based cultures towards ones that are flatter, more decentralized and inclusive, where people are encouraged to be learning-oriented, open to change, capable of having “courageous conversations”, and willing to embrace new ways of working.

For an organization to achieve this kind of change, its leaders must embody the change they wish to see — leadership behaviours are critical in reshaping culture. As Alain Bejjani, group chief executive officer of Majid Al Futtaim Holding, says: “As a leader, you not only have a critical role, but a very personal stake in your company’s readiness to handle the challenges of business cycles. To be successful as a leader is to continually challenge yourself to learn, to embrace a mindset of curiosity and an openness to change. To do so enables the identification, adaption and adoption of new ways of working, thinking and seeing the world around you. Without this, you are doomed to fail.” Bejjani stresses the importance of stretching people and ensuring that they benefit from an ‘outside-in’ view of the business. “Perhaps most importantly, your role is to actively contribute to a culture that sees learning and self-development as a means to personal, professional and organizational growth.”

You have to invest a lot in people, you have to communicate, help them develop their skills, help them to be committed to do these things, you have to set standards for what good looks like, you have to give them a clear roadmap in order to get there.

When Dr Mohsen Sohi, CEO of Freudenberg SE, took office, it was clear to management and shareholders alike that an evolution in the company’s organization and culture was necessary. While preserving Freudenberg’s long-term orientation, he set about implementing comprehensive changes in how the company was run. “I felt that a more agile, performance-driven organization would only be brought about by transferring decision-making power from the headquarters to the divisions where the actual entrepreneurial vigour of the company was most impactful and helpful to our customers.” He emphasizes that his role was only to be the catalyst. “My colleagues and I defined the processes and supported behaviours which brought about change. All the innovations were aligned with the company’s existing values; indeed, there were designed to make the values more real.” Through effective communication and the multiplying effect of getting the top 45 managers on board, the cultural change began to spread throughout the organization.

Culture and leadership are inextricably linked, so select and develop leaders who support the culture you want.

We don’t employ people who cannot identify with our values.

Despite its influence on business performance, culture is notoriously difficult to manage because the underlying drivers are usually hidden. Truly understanding the culture and diagnosing the elements of the culture that do or do not support the strategic priorities of the family business can unlock its full potential.

An important part of shifting culture in a certain direction is leadership selection, since the senior leadership team tends to have a disproportionate influence on the culture. If strategic or cultural change is on the agenda, family businesses can hire and promote leaders who will serve as catalysts for change. These leaders should possess the style preferences of the ideal target culture, but also have the influencing skills to model the right behaviours and bring along others in the organization. Bringing in a change agent from outside can be particularly difficult in a family business unless that person has the full backing of the owners who are, themselves, willing to model any desired changes in behaviour.

You must have a culture that enables people, making sure that they are at their best.

The most effective culture change leaders are credible in the current culture but also able to help push the culture in the desired direction. As Bejjani says: “Breaking entrenched practices and challenging ‘the way things are always done’ can require fresh eyes or a new perspective. Bringing about this shift means not simply onboarding new people, but identifying the organizational culture that will drive your company’s success and seeking the talent that reflects those aspirations to become an agent of the change you want to see.” Recruiting people into a family business always carries a risk, particularly at senior management level. Our research shows that in around 70% of cases where executive hires do not work out, cultural factors are involved. When bringing someone into the business, it helps to have a clear definition of the existing culture and to be able to articulate the desired culture if change is needed. Only then is it possible to assess an individual to determine their potential cultural impact on the organization.

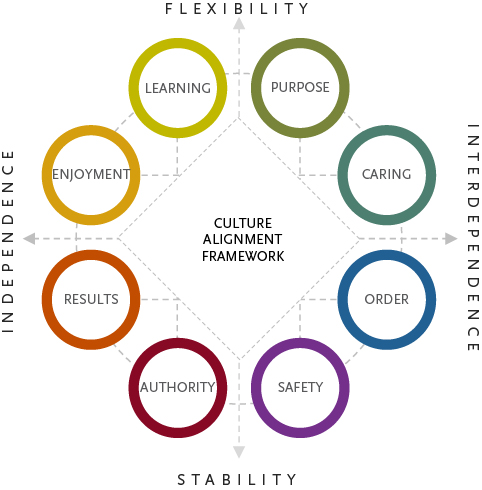

The culture framework developed by Spencer Stuart directly connects individuals to the culture by using the same language to describe both organizational culture and the personal styles of individual (see box-out).

Diagnosing culture helps de-risk recruitment decisions

An organization’s culture can support or undermine its business strategy. We help clients assess the alignment of culture and strategy, establish a target culture and evaluate the degree to which executives are likely to fit with, adapt to and shape culture.

Our framework for assessing culture is rooted in the insight that each organization and each individual must address the inherent tension between two critical dimensions of organizational dynamics:

-

Attitude toward people, from independence to interdependence

-

Attitude toward change, from flexibility to stability

Applying this fundamental insight, we have identified eight primary and universal styles, which can be used to diagnose highly complex and diverse behavioral patterns in a culture and understand how an individual executive is likely to align with that culture.

Each style represents a distinct and valid way to view the world, solve problems and be successful. While no single style can fully depict a culture or personal style, individual styles and organizational cultures tend to be more heavily weighted in two to three styles that reflect their orientation toward people and change.

For more information on Spencer Stuart’s approach, read ‘The Leader’s Guide to Corporate Culture’, one of HBR’s 10 Must Reads of 2019.

Conclusion

Family businesses are facing the most turbulent, disruptive period in generations. They must make sure that one of their sources of competitive advantage — their culture — does not become a liability. During a time of change it is vital that a company’s culture remains aligned to its strategy. Failure to do so will almost certainly result in underperformance.

With the help of a simple but robust framework, it is now possible for any family business to define its existing culture, identify changes it may wish to make and measure progress towards a redefined, target culture.

Are you comfortable that you understand your culture sufficiently well to be sure that it is fully aligned with the direction of your business?

We are grateful for the following leaders who contributed generously to our research with their time and insight:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alain Bejjani

Group CEO

Majid Al Futtaim Holding

|

Juan March*

CEO

Banca March

|

|

|

Mohammed K.A. Al-Faisal*

President

Al Faisaliah Group Holding

|

Mads Nipper

CEO

Grundfos

|

|

|

Thomas Fischer*

Chairman

Mann & Hummel

|

Torben Østergaard-Nielsen*

CEOl

United Shipping and Trading Company

|

|

|

Charlotte Korsager Winther

Head of Communications

THE VELUX FOUNDATIONS

|

Mohsen Sohi

CEO

Freudenberg SE

|

|

|

Alexander Krautkrämer*

CEO

Bericap

|

|

* Shareholder