Almost 40 percent of global infrastructure investment is spent ineffectively due to bottlenecks, lack of innovation and market failures, according to a recent McKinsey study.

To gain further insight, we spoke with leaders in the infrastructure industry across the U.K., Australia and North America to understand: “How has infrastructure become so inefficient, and what role does culture play in helping it catch up?”

Clearly, the industry needs to address its external-facing processes to reduce the productivity gap and navigate the ever-shifting business environment. At the same time, one of the largest challenges facing the industry is the prevalent organizational culture.

“In general, the culture is backward-looking, introspective, unwelcoming of new ideas and the initial reaction to change is resistance,” a former construction company CEO told us.

“Essentially, he who shouts loudest wins.”

This mentality may have been practical in simpler times, but it is no longer productive in today’s increasingly complex world. Competitive projects involve more stakeholders and place more emphasis on collective outcomes, which means leaders from across organizations and functions need to work more closely together than ever before. Indeed, change is not optional for some: the high rate of M&A activity means that some companies must face the challenge — or, to some, the opportunity — of integrating very different organizational cultures. (See sidebar on Culture and M&A.)

"In general, the culture is backward-looking,

introspective, unwelcoming of new ideas and

the initial reaction to change is resistance.

Essentially, he who shouts loudest wins."

a former construction company CEO

In our conversations, we found that leading companies are making culture-shaping more of a priority than ever before, hiring leaders who can champion and catalyze culture change, and increasing inclusion and diversity within their talent and leadership pools. Some companies are also attempting to rethink the company’s working relationship with external partners and contractors to embrace contracting based on alliance rather than opposition — a cultural shift that will only be possible if company leaders and employees are ready to work within a new, forward-looking paradigm.

The importance of culture

A key step in evolving culture is to simply acknowledge its importance and agree to work on it. As noted in this article published by Spencer Stuart in partnership with Harvard Business Review, a productive culture that’s aligned with strategy helps an organization in myriad ways: “When properly aligned with personal values, drives and needs, culture can unleash tremendous amounts of energy toward a shared purpose and foster an organization’s capacity to thrive.” As has been said many times, “culture eats strategy for breakfast.”

Unfortunately in infrastructure, the actual work of driving cultural change is often overlooked. “No one has bad intentions about culture, but it’s often put on the back burner,” one construction leader told us. “It’s such a thin-margin business that culture never gets to the forefront.”

As infrastructure companies embrace more collaborative approaches to working with clients and one another, culture will become more important out of necessity. Mindsets and processes within organizations will need to evolve to be more nimble and creative, and companies will need to engage early with all stakeholders. For many companies, such a model will require a shift in culture — and maybe a drastic one.

Making such changes won’t be an easy step for some more traditional leaders, who may find it difficult to alter their long-established ways. “There are pockets of leaders who are quite skeptical of the collaborative approach," said Nick Roberts, president of Atkins, a member of the SNC-Lavalin Group. "Not everyone is convinced that an open style achieves results. Instead, they prefer a much more top-down approach to getting things done.”

The contract affects the culture — and vice-versa

One manifestation of the traditional mindset — and an example of the way infrastructure is changing — is the prevalent contractual framework, which sets up a largely adversarial construct from the outset. The dynamic puts the risk on the contractor and creates a zero-sum game of “I win/you lose.”

Culture and M&A

The issues that come with blending dissimilar

cultures are becoming more important given the high

rate of mergers and acquisitions in the infrastructure

sector. Mergers and acquisitions are occurring with

increasing frequency, especially in the U.S.: 94

percent of infrastructure firms said acquisitions are

part of their current strategy, and nearly half said they

had made an acquisition during the past year,

according to a recent survey by FMI Capital Advisers.

These transactions create questions about which

cultural elements are worth keeping, which need to

be discarded and the difficulties that lie in creating a

new culture from the newly merged organization.

“There have been so many acquisitions that we’re

merging cultures all the time. It almost feels like

we’re trying not to destroy cultures of companies we

bought more than we are trying to create one,” said

a group president of a global construction firm.

“Often, there are positive things in cultures that you

don’t want to get rid of.”

Working with many different cultures can be arduous,

but it can also present an opportunity for a company

to create a culture that aligns with its strategic goals.

“I think this level of integration can be an enabler, if

done well,” said Shelie Gustafson, chief human

resources officer at Jacobs Engineering. “And if it's

not done well, it definitely will be a distraction.

Culture integration gives us an opportunity to look at

all aspects of our business, including systems,

processes, tools, approaches and policies. It helps us

choose the best of the best from both organizations,

or even a better way forward that only becomes

evident in the course of consideration. And it creates

an interesting tension that can spark innovation.”

Sometimes, the best approach may be to create a

new organizational construct that doesn’t try to

subsume different culture into one existing culture.

TC Chew, global head of rail for Arup Group, worked

on an English consortium project where “every

company in the consortium had its own culture,” he

recalled. To address this potentially vexing issue,

Chew said, “We set up a special purpose vehicle

(SPV) to specifically create the new culture.”

This mentality trickles down through organizations, affecting individual mindsets and organizational cultures (which in turn reinforces the combative contract process). The dynamic also undermines the risk-taking required to implement new technology, particularly considering the ever-escalating input and construction costs.

It’s becoming clear that an alternative contractual arrangement could lead to a healthier, more collaborative dynamic, which is driving some to move toward a new process. Some companies in Asia and the U.K. have adopted the Institution of Civil Engineers’ New Engineering Contact (NEC) system, which establishes a “family” of contracts that define the legal relationships and respective responsibilities of all parties involved. In this arrangement, parties to the contract have an equal voice and share in the performance of the collective — across the infrastructure sector — as a whole.

This type of contract requires strong leadership, a deep understanding of the involved cultures and a leap of faith from industry players. Ventures that have successfully created such a partnership include the Anglian Water @one Alliance, an England/Wales collaboration that formally links Anglian Water Asset Delivery with six key contractors. Created in 2015, this unique arrangement achieved annual savings of up to 3 percent in its first two years and reduced operational carbon output by 41 percent (a benchmark for the entire sector). Also using this contract is the city of Hamilton, New Zealand, which recently began a large-scale, 10-year infrastructure project that could eventually create nearly 4,000 new houses and save $70 million in interest.

Other cultures can serve as inspiration for less onerous contractual arrangements, as well. “Contracts in Scandinavia tend to be open, simple and straightforward, and that simplicity starts at the beginning. When they have a legal issue, they just sit down and talk about it and get it resolved,” said Mike Putnam, former president and CEO of Skanska UK. “Here, we have an army of lawyers who come up with additional clauses that make things too complicated.”

Culture matrix: where does your organization stand?

Culture matrix: where does your organization stand?

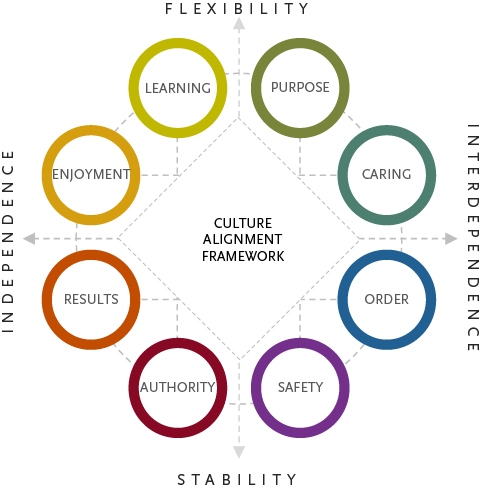

Spencer Stuart has identified eight primary and universal styles that can be used to diagnose highly complex and diverse behavioral patterns in a culture. As seen in this organizational culture model illustration, traditional infrastructure organizations tend to belong in the lower-left quadrant. The current dynamics in infrastructure call for a shift in culture towards the upper right quadrant.

The first positive steps

These collaborative contracts symbolize the direction infrastructure companies must move in an increasingly complex world. Changing culture is a crucial step in this process, but clearly that can be challenging: Many organizations lack an understanding of what culture really is and the tools necessary to evolve it. To shift their culture, organizations must be able to articulate what their culture is today and whether it supports the strategic priorities.

Evolving culture entails taking a longer-term view of the business and its strategic goals, which could mean exchanging lower short-term returns for greater gains down the road. That philosophy must be adapted by the management team and board if it is going take root.

“You have to look at, what are the vision and values of the executive team and the board?” said Simon Kirby, former COO of Rolls Royce and former CEO of High Speed 2. “You’re not going to be collaborative if the top executives are short-term focused, because they won’t be looking for anything beyond what’s right in front of them.”

Infrastructure companies can look to other industries for examples of longer-term thinking and practices. Several automotive and aerospace companies, for instance, have successfully incorporated collaboration and innovation into their cultures. As automotive manufacturers build more autonomous cars, they are being creative in their talent searches: A recent article described one company that hired an ophthalmologist to work on autonomous car lenses.

How does culture actually change?

Cultural change must come from the top, but it requires more than directives from the senior team. Leadership will have to foster a collaborative approach that values and applies different perspectives. This may be difficult for leaders who have come up through the old-school ranks of infrastructure and are acclimated to the win/lose dichotomy of the older mindset.

“It takes a certain type of leader to bulldoze through and keep a project on-track, but then you reach a stage where that type of leader has to pivot to a different way of thinking,” said Sean Donohue, CEO of the Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport. “It becomes, ‘Now that conflict is done, how do we bring people to the table and work together?’ And maybe they don’t have that ability — maybe they’re really good at bulldozing, but when it comes to getting people to work together that’s not in their skillset. So that’s something you’ve got to be aware of.”

Indeed, organizations will need to find leaders who can bridge these two ways of thinking: in other words, they can move a company forward in a more open, collaborative way while still engaging with the older mindset. “Dealing with that prior way of thinking becomes a key competency for people who interface with those customers, and it affects how they develop and maintain those relationships going forward,” said Paul McIntyre, global people director at Houston-based WorleyParsons.

It’s clear that leaders must model behavior and engage in it every day, rather than simply just dictate that change must happen. “Changing culture takes a long time, and it takes a very strong, concerted effort,” said Gordana Terkalas, senior vice president of human resources at Aecon Group in Toronto. “There’s a perception that introducing some very basic management activities equate to shifting culture, and that alone is not the case. You can design mechanisms to help reinforce what you want to achieve from a cultural perspective, but in fact it’s the everyday behavior of our leaders that will have the most impactful influence.”

Another key element in changing culture is to expand diversity, in order to include a wide breadth of perspectives. A growing number of infrastructure companies are looking to increase diversity within their talent and leadership pools and foster an inclusive culture. “Diversity is a key for us — both gender and cultural diversity has been an ambition from day one. We need to make sure that those voices are heard,” said Mark Elliott, CEO of Northwest Rapid Transit in Sydney, Australia.

Some companies are looking to become flatter and more matrixed in order to encourage more feedback within the organization. “Historically, BHP Billiton was more of a ‘top-down,’ directive style, but over the last few years we have made a deliberate change in our approach and we are now investing our people development efforts into creating a much more inclusive place to work, with more diversity,” said Matt Furrer, VP Projects for BHP Billiton in Brisbane, Australia. “We are giving everyone a voice, asking people to engage in idea generation around how we can perform better in the future. We want an environment where everyone feels empowered to contribute.”

The ambiguous ‘people stuff’

Working with culture is not an easy task, as leaders who have come up through infrastructure tend to have an engineering background, which has a reputation as being more literal and concrete and less intangible. As Terklas said, “I love working with engineers — often, what they do is spectacular technical work. Meanwhile, they tend to shy away from ‘people stuff’ that’s in more of a grey area. The profile of leaders we’re looking for today is very different from the leadership profile of the past. Now, we’re seeking more versatile competencies, such as adaptive thinking, emotional intelligence, change-leadership and the ability to lead diverse teams. This mix, combined with relevant industry experience, is becoming increasingly challenging to find.”

To create true change within an organization, the leadership team needs to model the culture and embrace the same discipline around culture as they do for other key performance levers, such as strategy and operations. Ideally, conversations about culture are integrated into the natural flow of business — during regular management team meetings, the annual strategy session and other follow-up strategy discussions. While a one-day workshop is not enough to evolve the culture, retreats and seminars focusing on culture can bring along the larger team on the need for a culture shift.

“We have these partnering sessions, which are basically retreats where you go somewhere and you get to know the people on the team, and you learn some processes and you come out of there on good terms,” a construction leader told us. “I’m convinced people who have been with us forever roll their eyes, but personally, I think it’s a good start.”

Conclusion

Infrastructure companies need to embrace a management discipline around a new, more nimble and collaborative culture. In doing this, they should articulate a culture target, select and develop leaders who align with the target culture, and reinforce the culture through organizational design and processes. They should also engage early with the client and explore alliancing, which requires strong leadership but can bring many benefits.

If infrastructure companies can adopt these changes and move toward a more open culture, they may well find they can ride the waves of change rather than being overwhelmed and left behind.